ARTICLES

Why new features are a bit like rainbows (and how to find solid gold bugs at the end of them)

- 7 minutes read - 1338 wordsI’ve been doing a fair bit of thinking recently about testing new features in software. New features are special. They are all shiny and new which means its very unlikely they will have been tested before. It can be insanely difficult to measure something new, especially if there is nothing similar to which it can be measured to against. Over the years I have seen many new ideas and designs translated into software and many test teams trying their best to test them. I would say that the number one cause of friction between departments, rivers of tester tears and silly quantities of overtime is adding new features to software.

So why is it so hard testing something new? Lets try understand the testing process for a new feature. Testing a new feature generally involves some kind of document that describes the feature and tells everyone what it should do. At a very basic level most people that don’t test (and even some newbie testers) will imagine testing a new feature as something like this.

The picture above makes testing a new feature look easy. Compare the software against the description of what it should do. Look at the good bits and raise bugs for everything which is bad. But something incredibly important is missing from this picture. As testers, we must keep in mind that the feature description is written by human(s). Writing a feature description that is all encompassing that explains every microscopic detail and is 100% flawless is just as impossible as testing software in an all encompassing way covering infinite amount of paths in microscopic detail. It can’t be done.

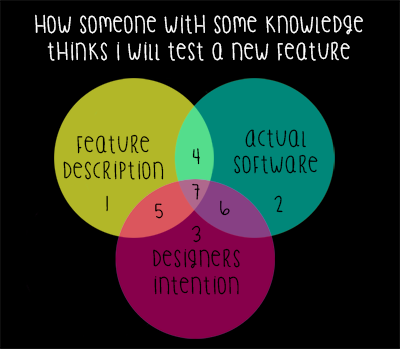

So, as testers, we need to give consideration to the designers intention. Once we start thinking about the designers intentions as well as what feature description says and what the software actually does. The picture now starts to looks a bit like this…

Seven distinct possibilities have been identified when testing the new feature. I’ve numbered these outcomes on the picture above.

Lets imagine we have a new feature. This feature is a clickable button in the software labelled ‘P’. When the tester starts testing they end up in one of the coloured blobs on the picture. This is where things can start to get a little confusing so please forgive me but I’m going to colour my text to match the blobs in the picture.

1) The designer does not intend this button to print when clicked. The feature description says the button should print when clicked. When the tester clicks the button, it doesn’t print.

2) The designer does not intend this button to print when clicked. The feature description says nothing about the button printing. When the tester clicks the button, it prints.

3) The designer intends the button to print, but doesn’t say so in the feature description. When the tester clicks the button, it doesn’t print.

4) The designer does not intend the button to print, but the feature description says it should print. When the tester clicks the button, it prints.

5) The designer intends the button to print, says so in the feature description but when the tester clicks the button it does not print.

6) The designer intends the button to print but does not say so in the feature description. When the tester clicks the button, it prints.

7) The designer intends the button to print. The feature description says the button should print when it’s clicked. The tester clicks the button and it prints.

Straight away, we’ve identified there is a lot more going on in the testing process than just comparing software to a feature description.

So what can happen in all these different circumstances? Hmmmm, my guess would be something like this..

1) Tester raises bug, the designer may see the bug and close it straight away. (chance of tester tears as tester thinks “the designers are closing my bugs for no reason”)

2) Tester must question the designer “is this button supposed to print?” some lesser testers may fail to ask this question (chance of friction as designer thinks “did the tester not read the feature description properly?” regardless of whether or not feature description contained the answer)

3) Tester doesn’t see a problem, nothing in the description indicates a problem (chance of friction with additional tester tears as only the designer can see the bug. The designer may change the description in the middle of testing, or start raising their own bugs. When designers raise bugs sometimes they forget to mention critical information and testers don’t take ownership of them. They can slip through the normal process net and slowly rot in a bug the database as no-one really knows what to do with them.)

4) Unless the test team has developed psychic powers, only the designer will see the bug. (chance of friction and tester tears. The worst scenario is that someone blames the test team for missing a bug they had no chance of ever seeing)

5) Bug raised, no further questions required. Sadness is deflected from the test team on to the programmers instead.

6) Bug raised that says the software does not match feature description (chance of friction when designer tells tester their bug is “as designed”)

7) Everyone is happy!

When you look at the big picture and see that only 1 of 7 possible outcomes results in happiness for testers, designers and programmers. You start to realise that there are a lot of things that can make the team sad. Maybe if more people were aware of what was actually happening they would be able to avoid some of the associated problems.

I know when I test a new feature, the testing I do takes everything mentioned above into consideration then something special happens. The special bit happens in my head when I start applying my imagination, creativity, logic and common-sense. I suddenly start seeing bugs that no-one else can see! If you were to ask most people to describe a rainbow, they would say that a rainbow is red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. They describe what they can see with their eyes. However a rainbow is more than just visible light. It has infra-red at one end and ultra-violet at the other and you can’t see these bits of the rainbow with just eyes. Our picture of testing a new feature now looks something like this…

Let me give you some examples of some things that happen when I test.

I’m looking at something right in the middle (Number 7 - designer intends it to happen, feature description describes it happening and it happens in the software) however this “feature” is making the software flash in such a way it’s making my eyes hurt and I think we could be sued for inducing epileptic seizures.

I see the button is green text on a red background and think this won’t be a fun experience for someone with colour blindness.

I see the Japanese version of the software contains an image of a Hong Kong flag and think people in Japan won’t like this. Just as a confederate flag would be bad in the American version or a Swastika bad in the European version.

I see a pink elephant’s trunk in a children’s game that is HIGHLY inappropriate and think no way will this get past PEGI/ESRB or any other age ratings board of classification.

In a browser based game I think I might be able to skip from level 1 to level 100 if I start changing numbers in a the URL query string.

And this my friends is the secret to finding solid gold bugs at the end of a new feature rainbow. If you can learn to think independently about the thing that you’re testing, you will start seeing the infra-red and ultra-violet bugs that no-one else can see or imagine.

This post was originally published on my software testing blog Mega Ultra Happy Software Testing Fun time.