ARTICLES

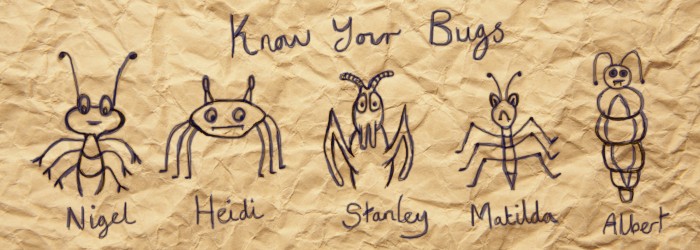

Know Your Bugs

- 4 minutes read - 772 words

As Software Testers, we have to frequently imagine the unimaginable. Through experience we learn, adapt and prepare for the next time we encounter similar circumstances. Recently, I found a particular annoyingly awkward bug and was able to draw from experience to not only identify but also explain very quickly without too much investigation why this bug was happening. I was able to do this as I had encountered an almost identical bug a couple of years previously. This made me start thinking about some of the trickiest bugs I had ever seen and their root causes. How common certain “bug patterns” were and how I would approach the symptoms of one of these “bug patterns” now compared to the first time I saw them.

I decided I was going to try document the behaviour, symptoms and causes of these bug patterns. Then I gave them silly names to help remember them.

The needle in a haystack bug - This is a rare bug which only occurs in a single very specific circumstance, but it avoids detection as it hides among thousands upon thousands of other circumstances which all work correctly. Imagine an input which accepts a value from 1 to 9999999 but only breaks if that value is specifically 4528183. These bugs tend to be stumbled upon accidentally and are generally found through a mixture of exploratory testing and pure blind luck.

The positively helpful bug - This is a friendly bug that instead of causing something to break, it makes something work exactly as was intended. No-one has spotted it exists because nothing appears to be broken. The positive helpful bug has been there for a significant amount of time. It keeps everyone happy by making software do exactly what it’s supposed to do. Until one day it is unexpectedly removed. Someone saw the bug while they were re-factoring the code and killed it. Now the positive helpful bug is dead, all the code is broken and no-one can easily see why.

The crouching tiger hidden bug - This is actually a combination of two bugs. The first bug is usually some kind of logic bug which prevents the code containing the second bug from ever executing. It’s only when the crouching tiger is fixed, that the hidden bug is revealed.

The longest journey bug - This bug usually makes it’s debut appearance towards the end of a long day spent performing exploratory testing. It appears once and only once. That is until a few weeks later, when it makes its encore appearance and no-one can work out why. The longest journey bug is essentially a bug that is tucked away at the end of a very long path. Surprisingly even though on the surface it appears to be unreproducible, it’s actually 100% reproducible. Only unlike a regular bug, the number of steps which must be followed to recreate it are in the hundreds or thousands. An example of a longest journey bug would be software which gradually increments a value as the software is used, until this value reaches a size that is just too big for the software to handle at which point the bug manifests.

The all the planets are aligned bug - This an especially rare bug that is conditional on a number of factors which rarely occur simultaneously, all occurring simultaneously. Imagine a date that only breaks when both the day and the month are 9 characters long. You would only ever see a problem with it on Wednesdays in September. Just like when all the birds stop singing during a solar eclipse, these bugs can feel quite weird when you experience them for the first time. Incidentally, the [19th January 2038] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Year_2038_problem) should be a fun day for anyone working with software that stores dates as 32-bit integers.

The far too obvious to be a bug, bug - This is the bug that doesn’t make any attempt to hide. It is and always has been in plain sight. Everyone on the team has seen it every day for the last 6 months. But for some reason it’s never been reported as a defect because seems “far too obvious” to be a bug. No-one says anything because “If that was a genuine bug, someone else would have already reported it by now”. It usually takes either a confident experienced tester to challenge the far too obvious bug or a naive new starter that is looking at the software for the first time to find these kind of issues.

This post was originally published on my software testing blog [Mega Ultra Happy Software Testing Fun time] (http://testingfuntime.blogspot.co.uk/)